To Screen or Not to Screen

When health screenings do more harm than good. And an interactive website for learning about suitable health screenings in Singapore.

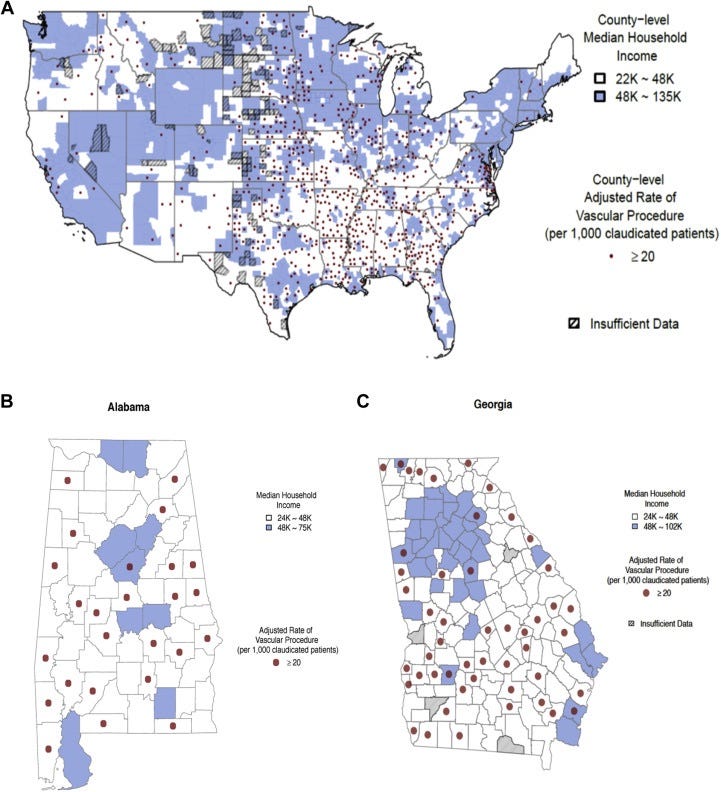

When researching for his book, The Price We Pay, Dr Marty Makary witnessed an unscrupulous practice. A lady from a local cardiology clinic was measuring the blood pressure in the arm and ankle of an African American churchgoer. On the surface, these free checkups appear helpful—until you realize they’re a tactic to exploit the trust of vulnerable patients for unnecessary treatments and financial gain.

The test, known as the ankle-brachial index (ABI), is not recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force due to a lack of evidence for its effectiveness in screening for peripheral artery disease. But treating for peripheral artery disease is lucrative. A doctor can make up to $100,000 in a single day from such procedures. The doctors didn’t seem to care that the screening is not recommended or the treatment is likely unnecessary.

Once the blood pressure test shows a little anomaly, the patient would be led down this perfectly legal scam. An ultrasound, then a Doppler study, then a diagnostic catheterization, and then finally a balloon. While the fees might be covered by Medicare or private insurance, the patient would have paid in psychological distress and discomfort since the free checkup at the church—for medical care they likely didn’t need.

Dr Marty Makary’s research team at Johns Hopkins dug deeper. What they found was infuriating. Most of the interventions were performed on people in low-income areas. A likely explanation? These vulnerable patients were being exploited by doctors for Medicare payouts.

This all started with that seemingly helpful but actually deceitful screening test.

This predatory phenomenon of overscreening isn’t limited to the US. Even in Singapore, a study found that 11 out of 14 healthcare providers offer screening packages with tests that are not recommended by Singapore’s Ministry of Health. These “comprehensive” packages, excluding any follow-up tests or treatments, can cost up to $10,000.

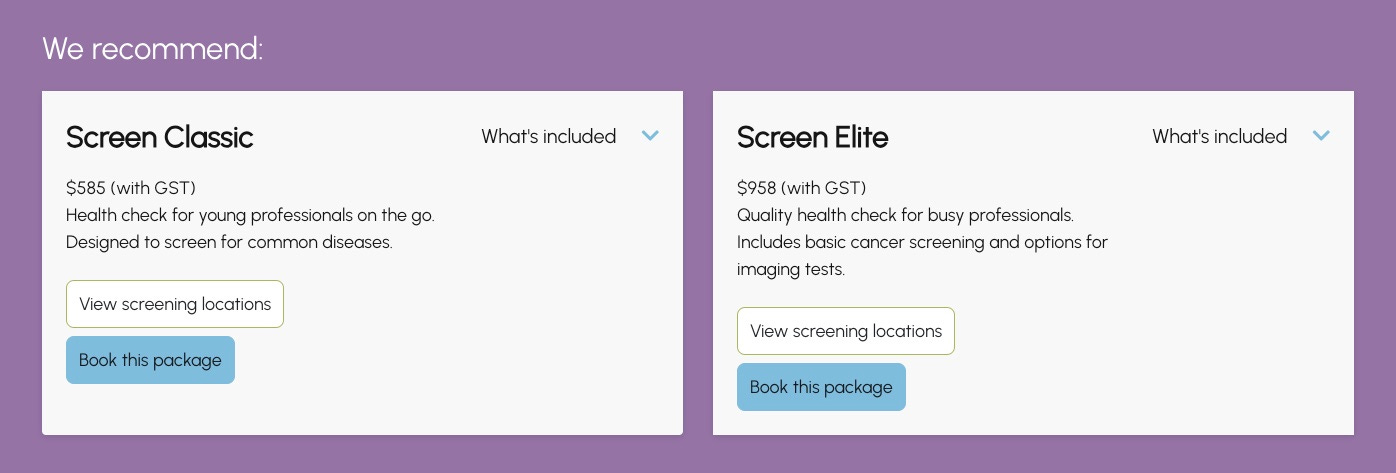

Intrigued, I went to a local provider’s website. On the health screening packages page, I selected “Men below 40”. As though waiting for a doctor’s advice, I waited for the website to load for a few seconds. Based on my profile—it knows nothing more than I’m a man below 40—it recommended two packages.

The more expensive package includes “basic cancer screening”. For a health-conscious and cancer-wary individual like me, that is more attractive. Except there’s an issue. According to the official guidelines, the three tumor marker tests included are either not recommended as a screening test (CEA for colon cancer), only suitable for Hepatitis B carriers or individuals with liver cirrhosis (AFP for liver cancer), or only appropriate for men with a strong family history of prostate cancer (PSA for prostate cancer). It gets more outrageous. There is an even pricier package ($1,700) with “full cancer screening” that includes more tumor marker tests that are not recommended (CA19.9 for pancreas cancer and EBV serology for nose cancer).1

More is not always better.

Overscreening harms more than helps

A couple of years ago, my heart felt off. Even a slow jog would spike my heart rate above 180. I was worried enough to get an ECG and blood test at a local polyclinic. Thankfully, besides my platelets being a little out of range, likely due to a cold, my heart seems fine. My wife, an emergency doctor, took a look at my ECG and lab results and confirmed I was fine. But I wasn’t convinced.

“Maybe I should do a full body checkup,” I mentioned to my wife over dinner one day. “Don’t be silly. You are young and fit. You don’t drink or smoke. The doctors won’t entertain you,” she educated me. “How about cancer?” After losing a few relatives to cancer, I felt the urge to guard against cancer as much as possible. “Oh, those tumor markers are not recommended for screening,” explained my wife. That comment got me down a health-screening rabbit hole.

To my surprise, I discovered that tumor markers are not only ineffective for cancer screening but also potentially dangerous. They often lead to false positives, which then lead to unnecessary physical harm, psychological distress, and over-treatment.

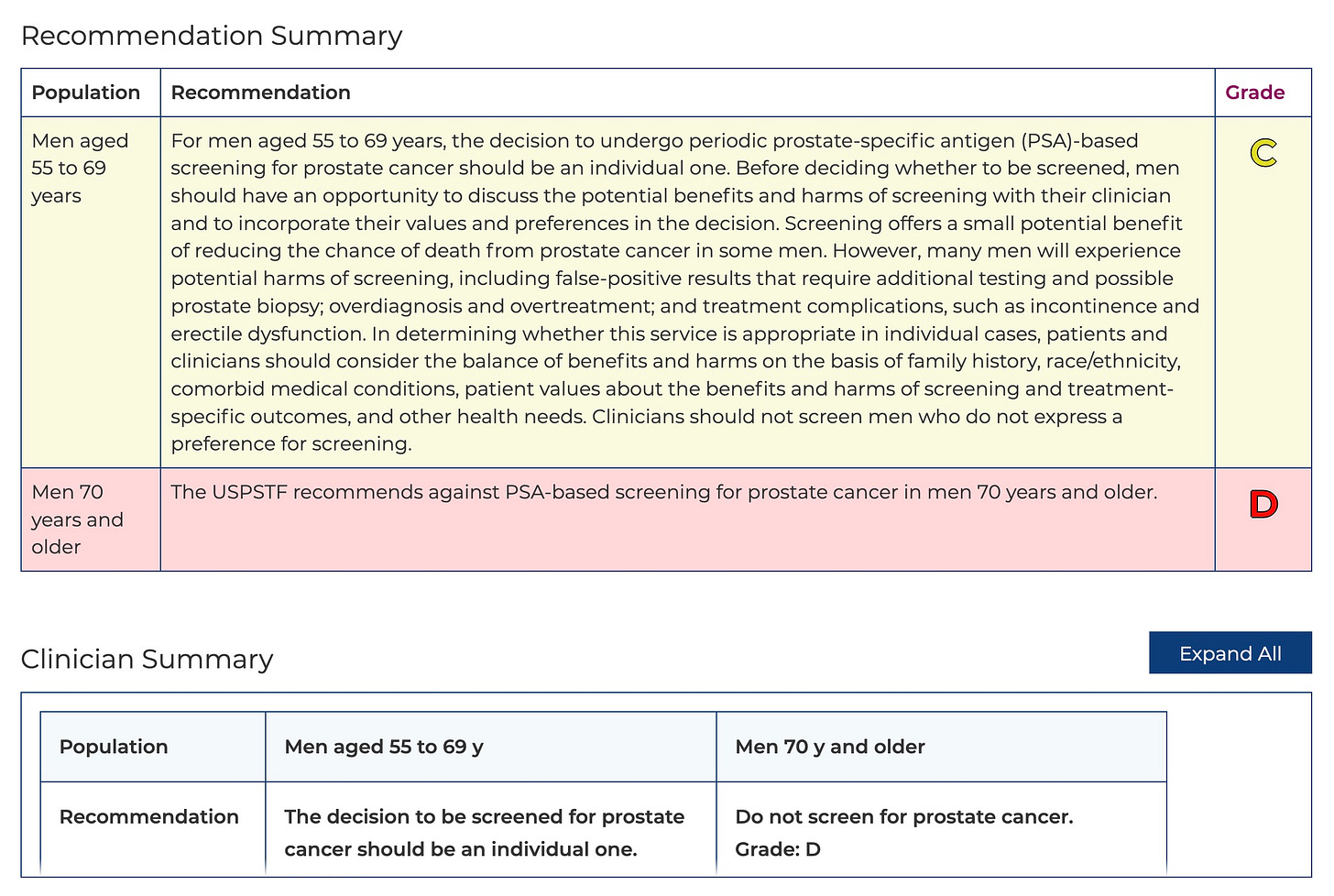

Consider Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA), a tumor marker for prostate cancer. Depending on which test threshold is used and how frequently the test is done, the false positive rate ranges from 11.3% to 46.6% to 75%. Why is it so high? Because simply cycling, ejaculation, or having an infection can elevate your PSA level. To rule out prostate cancer and to alleviate your anxiety, the doctor might suggest a prostate biopsy, an operation to collect tissue samples from your prostate for further analysis. While prostate biopsies rarely cause serious issues, the procedure is not entirely benign. For every 1,000 prostate biopsies, 21 men were admitted for complications and two died. Worse still, prostate biopsies have a relatively high false-negative rate. So even if the biopsy result is negative, you could still have prostate cancer. Bad? That’s not all. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care found that up to 54% of men screened are diagnosed with prostate cancer that may not progress and do not require treatment. But most patients, including those with the lowest tumor risk scores, are aggressively over-treated with radical surgery, radiation, or hormone therapy, causing issues such as urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.2

During my research, I stumbled upon an unfortunate case of a man who was misdiagnosed with a fatty liver based solely on his blood test results. (Screening for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is not recommended across various countries for the general population.) Because of the diagnosis, he was denied insurance. Desperate for answers, he went to a liver specialist to get an MRI and more blood tests. The devastating part? He never had fatty liver to begin with. All that fear, frustration, and financial loss—because of a false positive.

But the takeaway here is not that we should avoid harmful screenings altogether. We should understand the risks of the screening and weigh them with the potential benefits, with the help of our doctors and scientific research. Take colonoscopy as an example. It is proven to be effective at catching colorectal cancer early. But because the scope that enters our body might perforate our colon, it shouldn’t be done regularly. Since most growths in the colon take years to develop into cancer, colonoscopy is recommended only every five to 10 years.3

The price of overscreening isn’t just financial. It is also the fear, the anxiety, and the pain—all because of a test that should never have been done in the first place.

So, how do we know what screenings to do and avoid?

Scientific evidence-based screening recommendations

In the past, patients are more likely to adhere to their doctor’s suggestions without question. But with the abundance of information, that is changing. My wife often tells me how patients would read up about their symptoms before seeing her at the emergency department. While some doctors get annoyed by patients who trust unverified medical information on Google rather than their expertise, patients wanting to take charge of their health is a positive shift. However, it is still unrealistic for laypeople like you and me to study enough to select the suitable health screening tests ourselves.

Some screening tests are recommended for the entire population. Some are only appropriate for high-risk individuals or symptomatic patients. The ankle-brachial index test? Only for people with crippling leg pain and other serious symptoms.4 The ECG I did? Only for people at high risk of cardiovascular disease events. I wouldn’t have been able to get an ECG at the public polyclinic if I hadn’t complained about potential heart discomfort.

But how do we know?

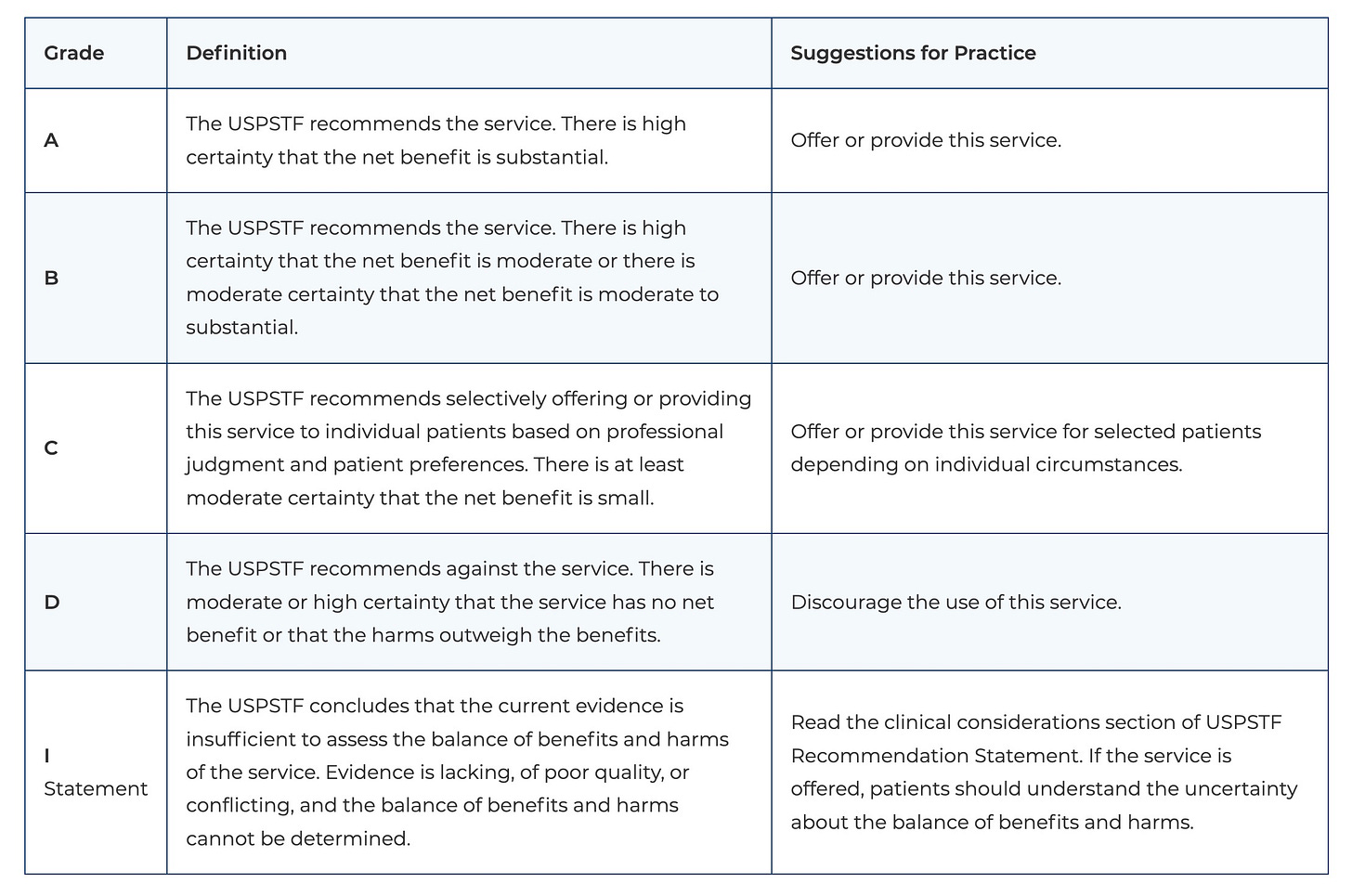

Thankfully, governmental organizations and expert groups around the world, such as the US Preventive Services Task Force, Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, the UK’s National Screening Committee, and Singapore’s Ministry of Health, have come up with health screening recommendations based on scientific evidence for their respective populations. Both to guide doctors and inform patients, these frameworks classify screening tests into easy-to-understand categories. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force uses five grades:

For each screening, the US Preventive Services Task Force explains the recommendation and links to supporting evidence.

Recommendations like these do not replace our doctors. They shouldn’t. But they provide us patients with a trustworthy second opinion, independent of our doctors.

Discover suitable screenings for you and your loved ones

The common advice—and the safest to say—is to consult a doctor. But I don’t think that is the best choice nowadays. As much as they want to, even kind-hearted doctors don’t have the capacity to sit down, understand our full medical history, and help us prevent illnesses. Given the abundance of legitimate information online, the best course of action is to first educate ourselves about what to look out for—and then consult a doctor.

Unlike the US and UK, Singapore’s Ministry of Health doesn’t have an interactive website for finding suitable screenings and understanding the recommendations in detail. It has a 93-page PDF report by its Screening Test Review Committee. Its Screen for Life website only allows you to enter your age and gender but not family or medical history, and it shows only tests suitable for the entire population.

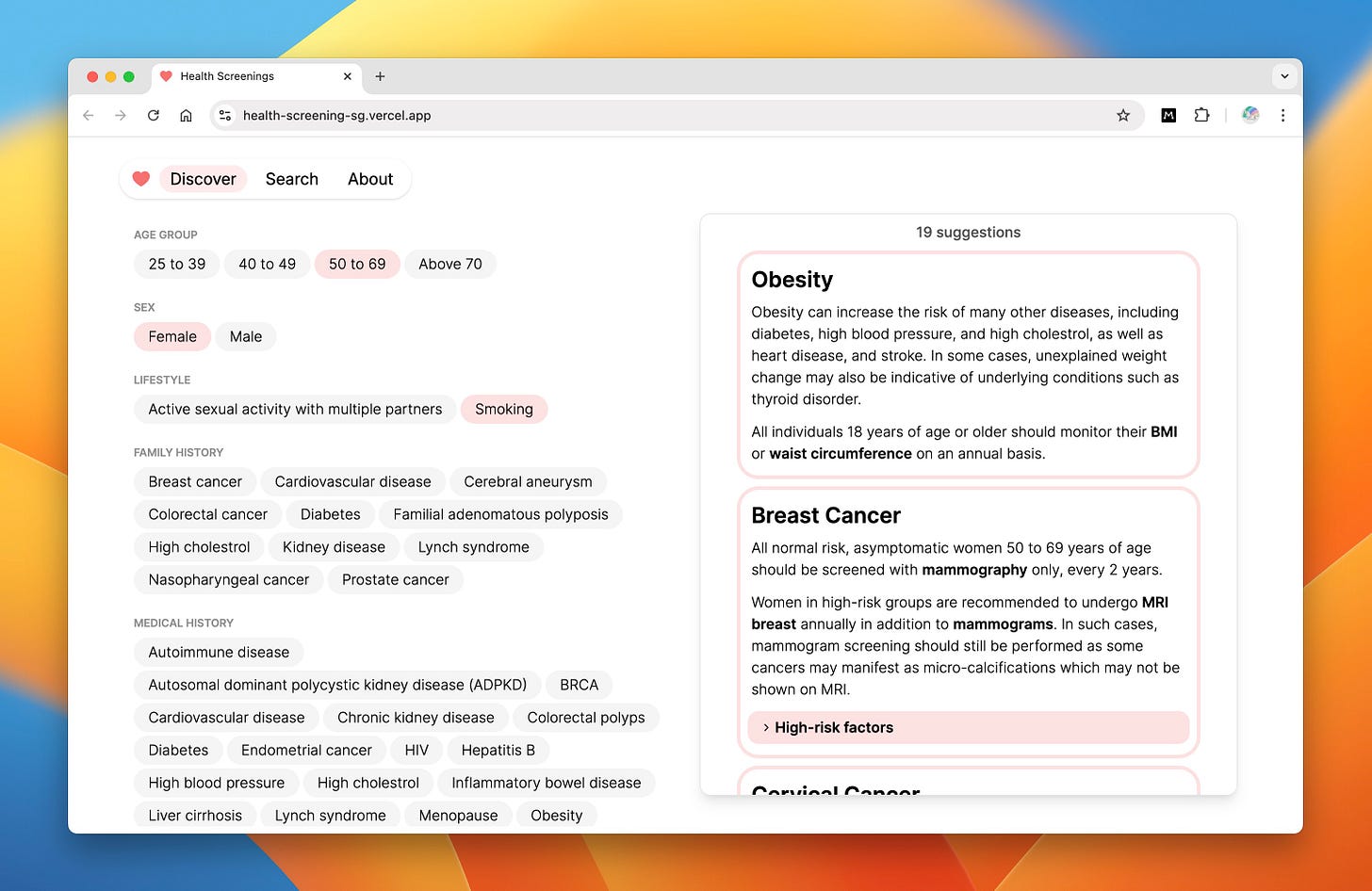

To help raise awareness of health screenings in Singapore and encourage more people to take charge of their health, we created an interactive website from the PDF report at https://health-screening-sg.vercel.app. This website allows you to select not only your age and gender but also your lifestyle habits, family history, and medical history. It will then suggest tests according to your selected profile, including tests for high-risk individuals.

(If your country does not have a health screening recommendation framework, you could use this as a starting point for your research.)

To get started, under the Discover tab, select your profile and see the various diseases you should screen for.

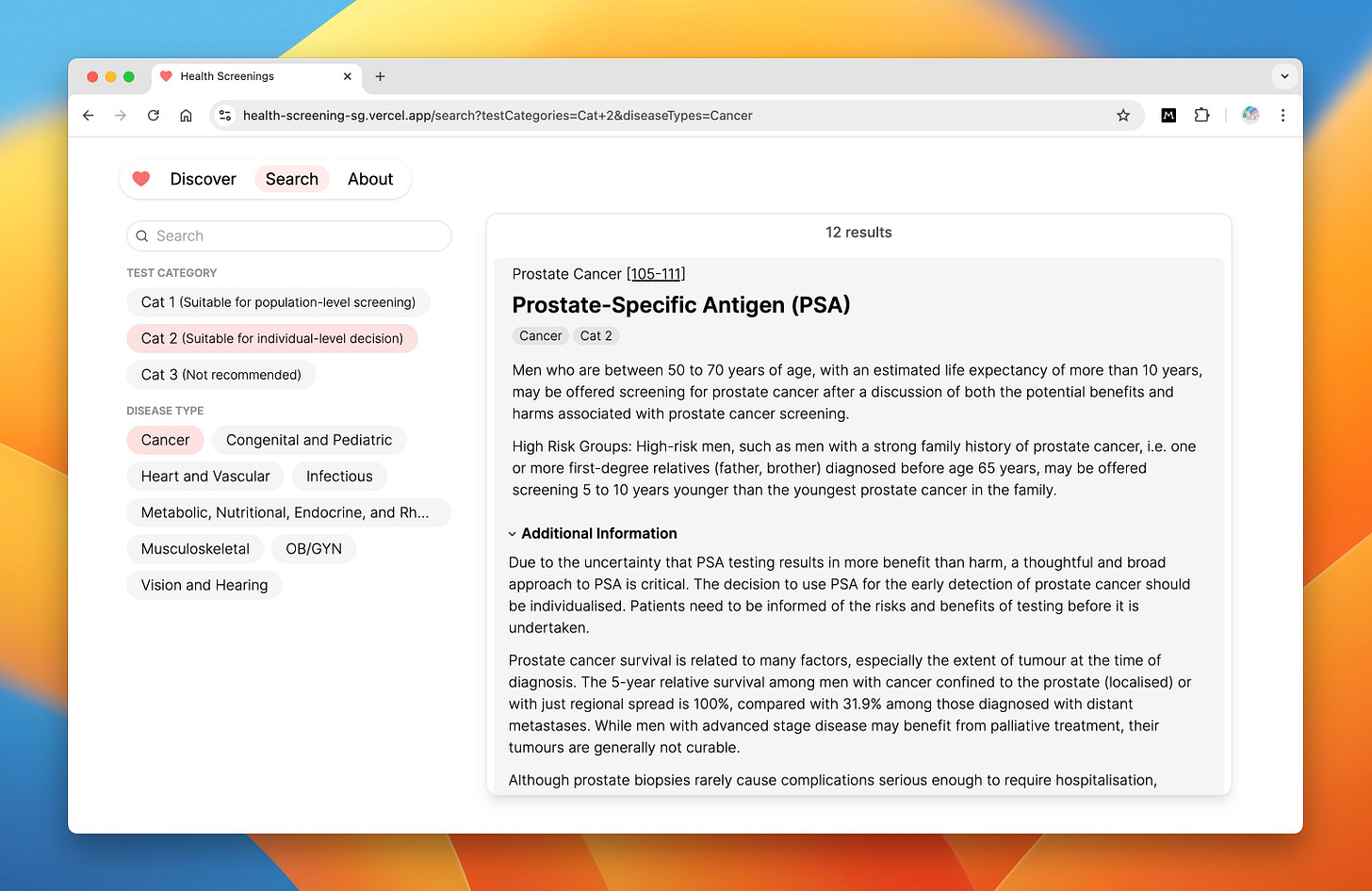

Once you have identified the diseases to screen for, you can search for individual screening tests under the Search tab and dive into the recommendations. Armed with these official guidelines, you can have a more informed discussion with your doctor.

We hope this interactive website will make understanding health screenings more interesting and prompt you to do further research and discuss them with your doctor. You can also use it to discover what diseases your loved ones—partners, parents, and children—should be screened for.

A senior doctor friend often reminds me, “Your health is your own responsibility.” We trust our doctors with our lives. But we also owe it to ourselves—and to our loved ones—to ask questions, to push for understanding, to demand better. No one else will live with the consequences of a false diagnosis or an unnecessary treatment. It’s our health. It’s our responsibility. And we must be its fiercest defenders.

According to Singapore’s Screening Test Review Committee, “Tumour markers for NPC (EBV IgA serology) should be combined with nasopharyngoscopy in the screening of high risk individuals. Serological tests alone, without endoscopy, are not recommended as a means of screening or monitoring of high risk individuals. As such, screening of high-risk individuals should be performed by a qualified specialist and include an appropriate history and examination, including nasopharyngoscopy.”

According to Singapore’s Screening Test Review Committee, “Men who are between 50 to 70 years of age, with an estimated life expectancy of more than 10 years, may be offered screening for prostate cancer after a discussion of both the potential benefits and harms associated with prostate cancer screening.”

Also, because colorectal cancer is rare in young people, colonoscopy is only recommended for people above 50.

This is taken from page 18 of The Price We Pay.